Voice Magazine for Women, a free, monthly publication distributed regionally in Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia to 650 locations, partners with the Birthplace of Country Music to promote our annual music festival, Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion. In August and September of each year, Voice generously allows us free rein to produce cover stories for the magazine highlighting upcoming acts performing at the event. With their permission, we have duplicated the cover article for this month – we hope you enjoy it! To read this month’s issue in its entirety, click here.

Voice Magazine for Women

Rosanne Cash: Americana’s Renaissance Woman

A Q&A on Family Ties to Southwest Virginia, Her First Trip to Bristol, and Fun Stuff You Didn’t Know and Would Likely Never Ask

By Guest Contributor Charlene Tipton Baker

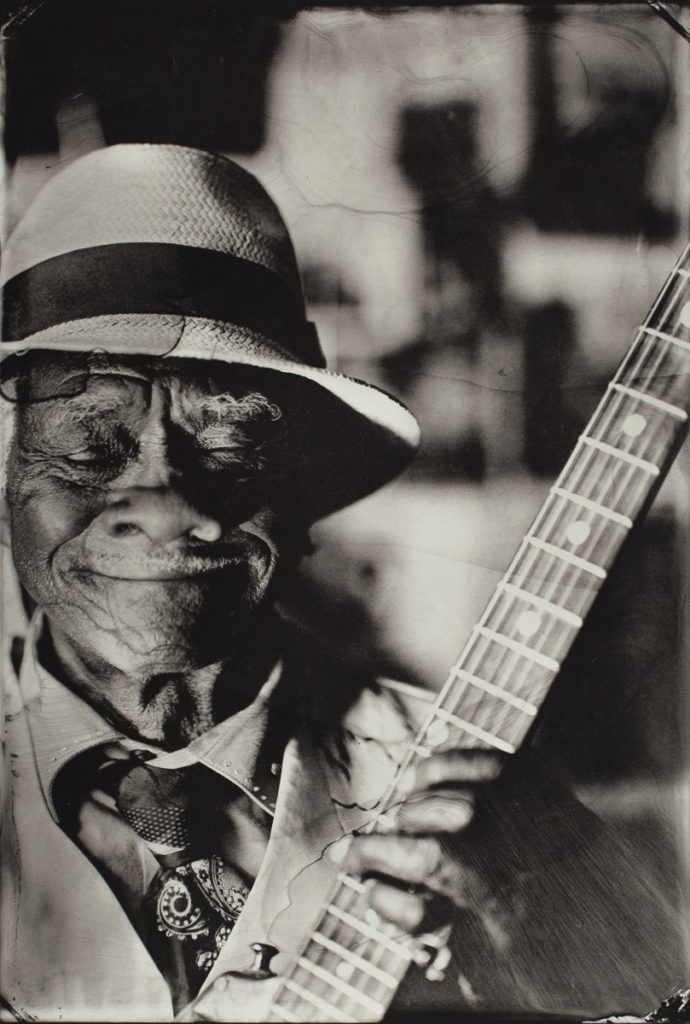

Photo Credits: Michael Lavine

Rosanne Cash is one of the most revered artists in Americana music. At 67, she has an amazing career as a multi-GRAMMY Award-winning songwriter and performer. A born writer, Cash was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2015 and is a bestselling author and poet. Her fiction and essays have appeared in The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and Oxford-American, among others, and she is frequently invited to teach classes in English and Songwriting at various colleges. Additionally, Cash is an advocate for creators’ rights and children’s causes, including education and gun violence prevention.

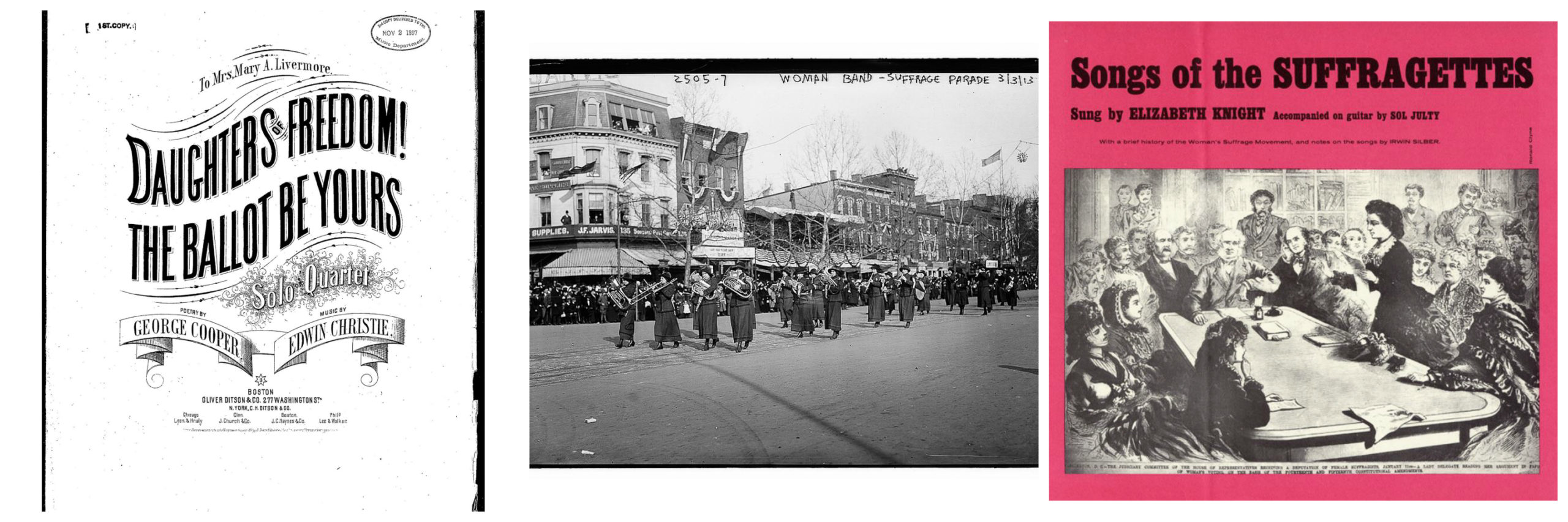

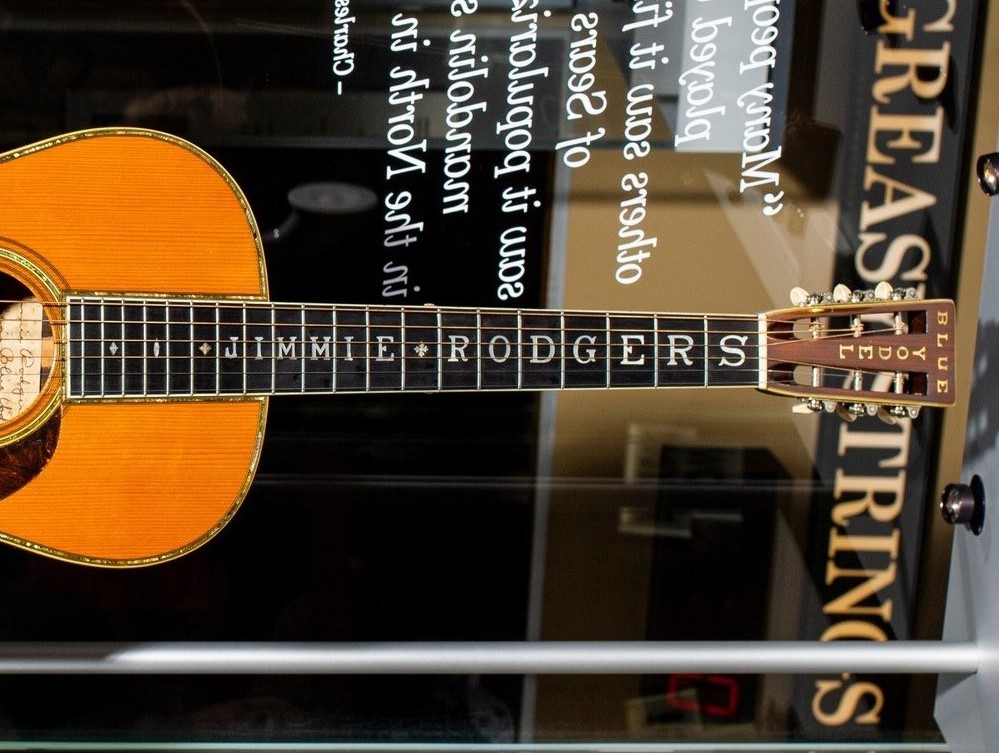

This September, Rosanne Cash headlines Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion on the 95th Anniversary of the legendary 1927 Bristol Sessions recordings. Rosanne’s familial connection to our region’s music heritage makes her visit extra special; she is the eldest daughter of country music legend Johnny Cash and his first wife Vivian. She also enjoyed a close, loving relationship with Johnny’s second wife, June Carter Cash. June is the daughter of Mother Maybelle Carter of the Carter Family, the “First Family of Country Music.” The 1927 Bristol Sessions included the very first recordings of The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, the “Father of Country Music,” and catapulted country music into the mainstream.

Ralph Peer recorded the 1927 Bristol Sessions in the Taylor-Christian Hat & Glove Company building on the Tennessee side of State Street. The building was long gone by the summer of 1971 when Johnny and June traveled to Bristol, alongside Maybelle Carter, Sara Carter Bayes, and other members of the Carter clan, to dedicate a monument to the 1927 Bristol Sessions at the site where they took place. Ralph Peer II (son of Ralph Peer) and members of Jimmie Rodgers’ family were also present. Thousands of people from the community gathered for the occasion. On that day, Johnny expressed to them how he would love to see a museum dedicated to the music history that had been made in Bristol.

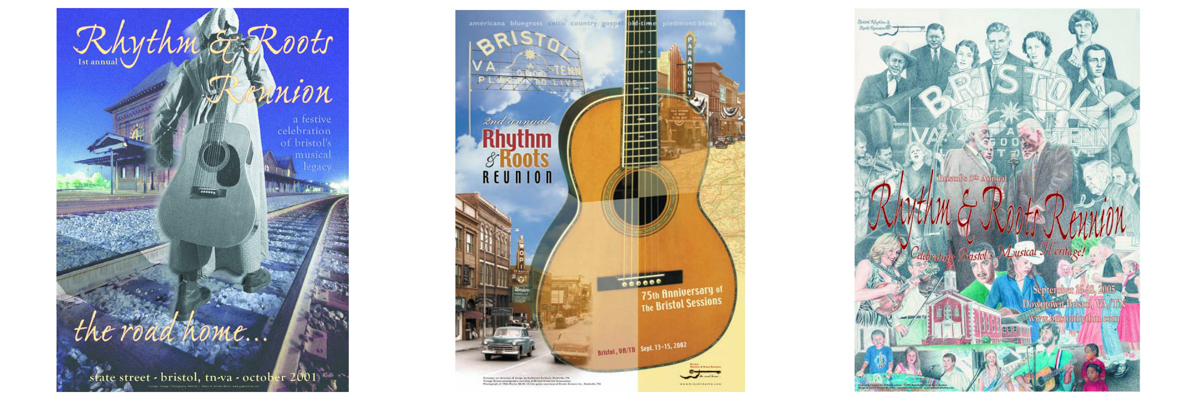

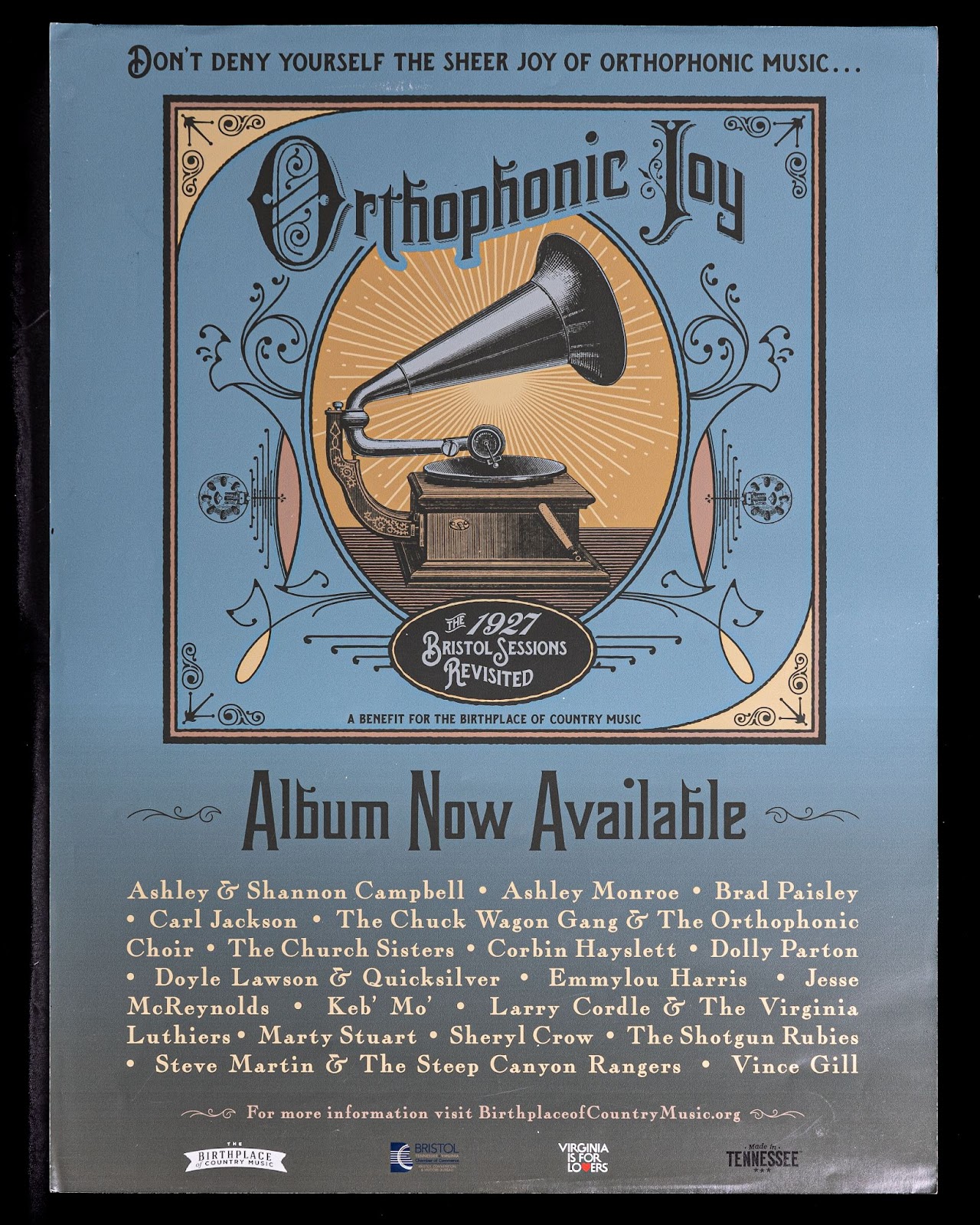

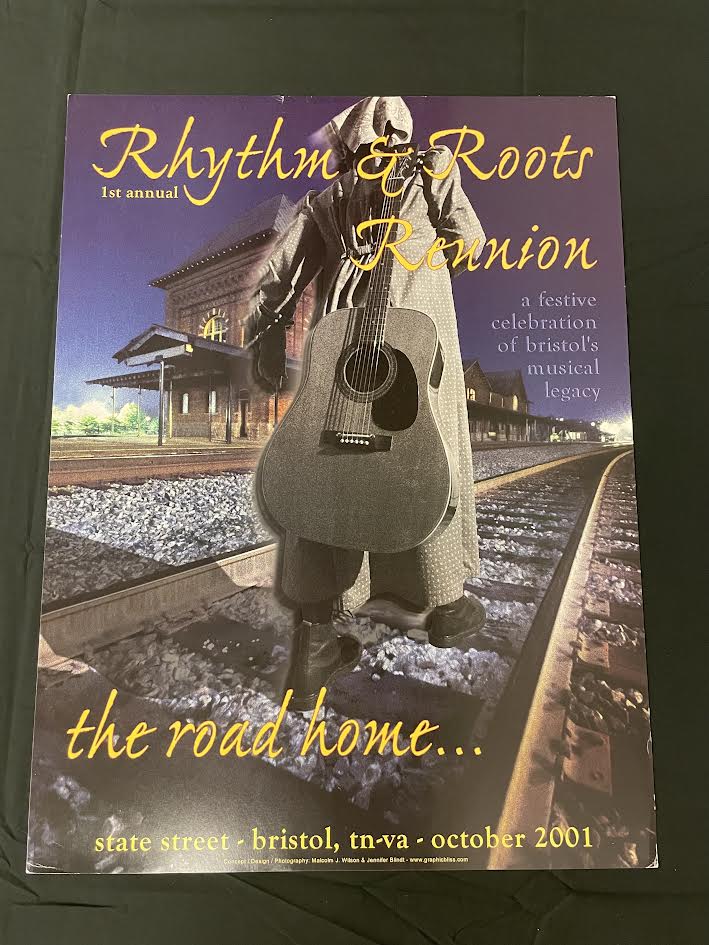

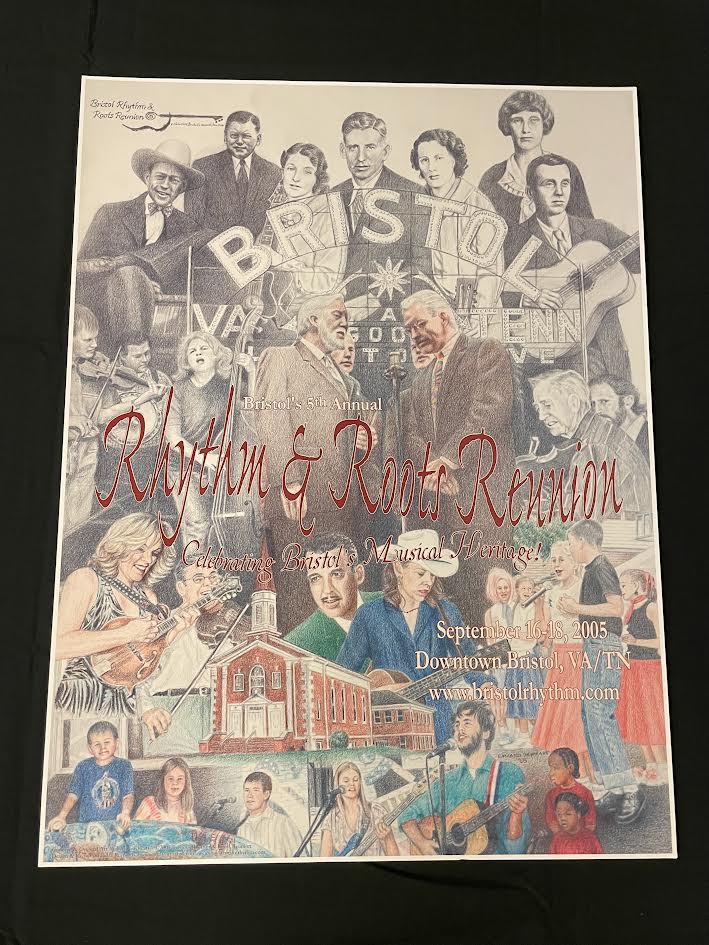

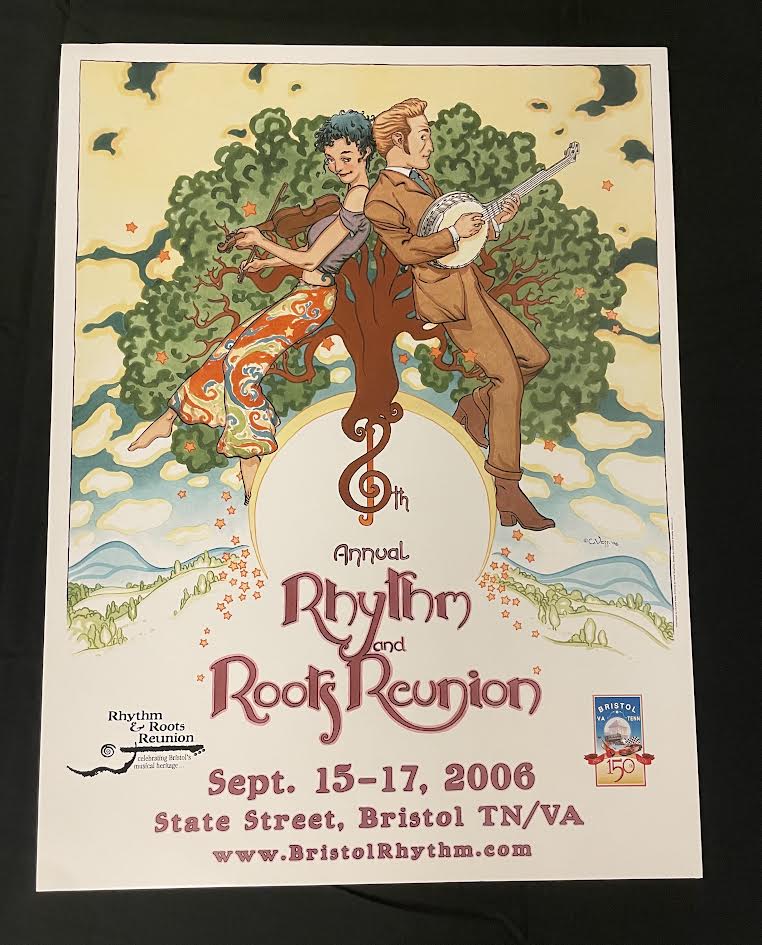

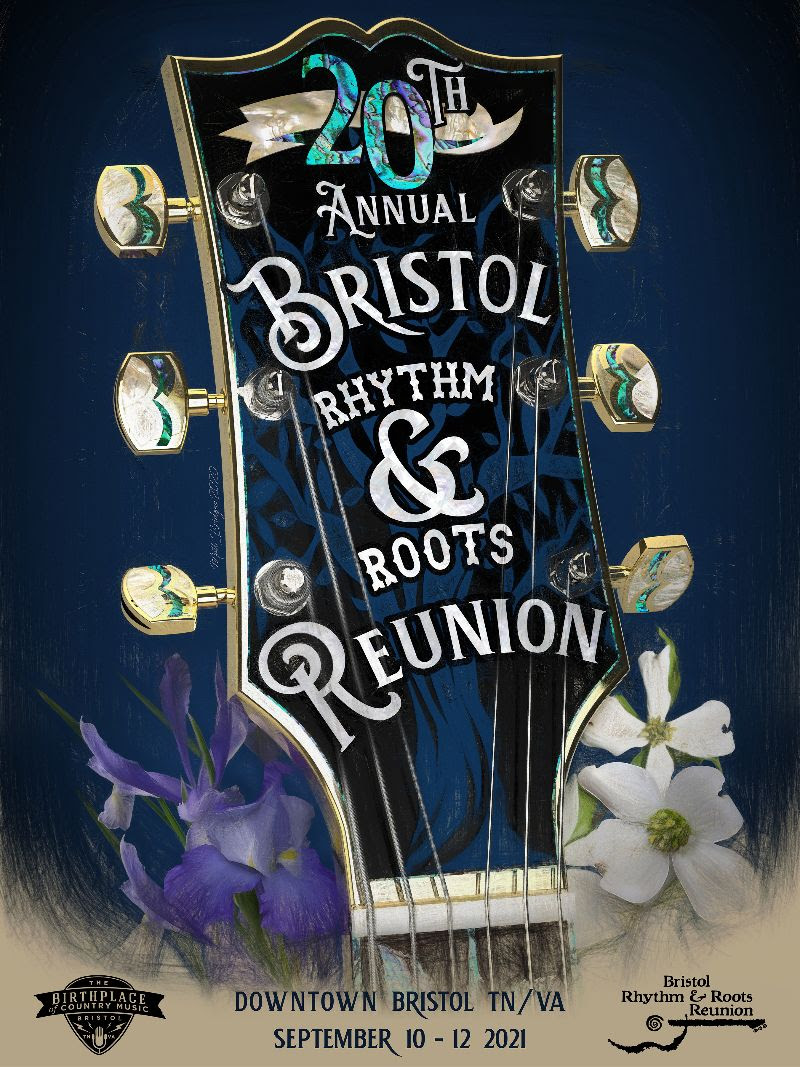

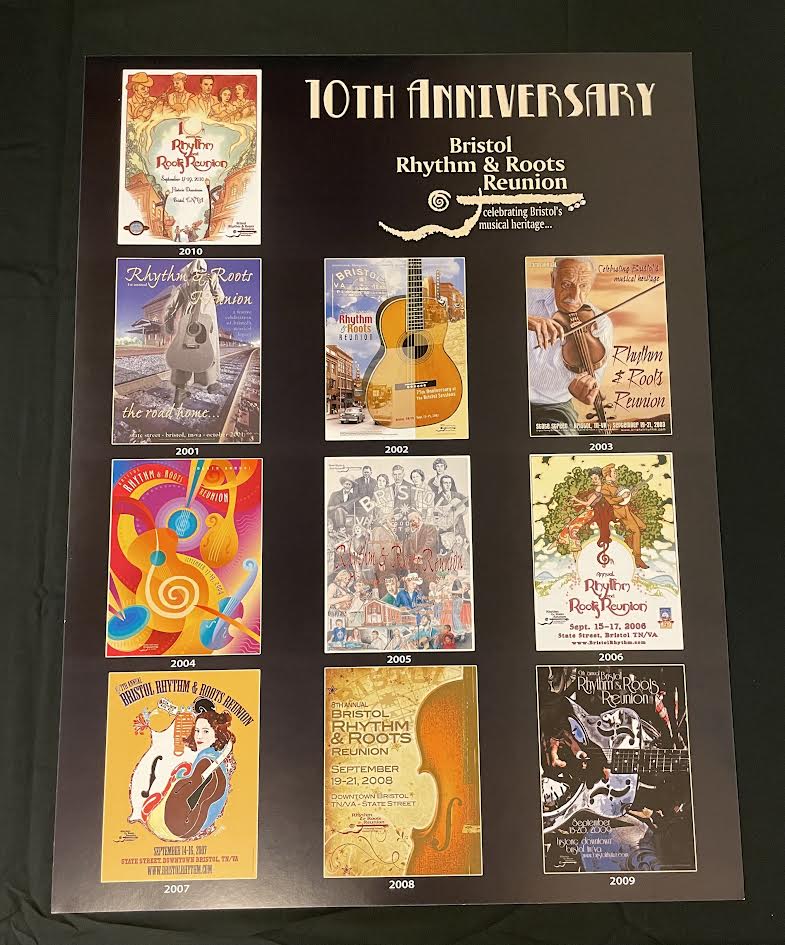

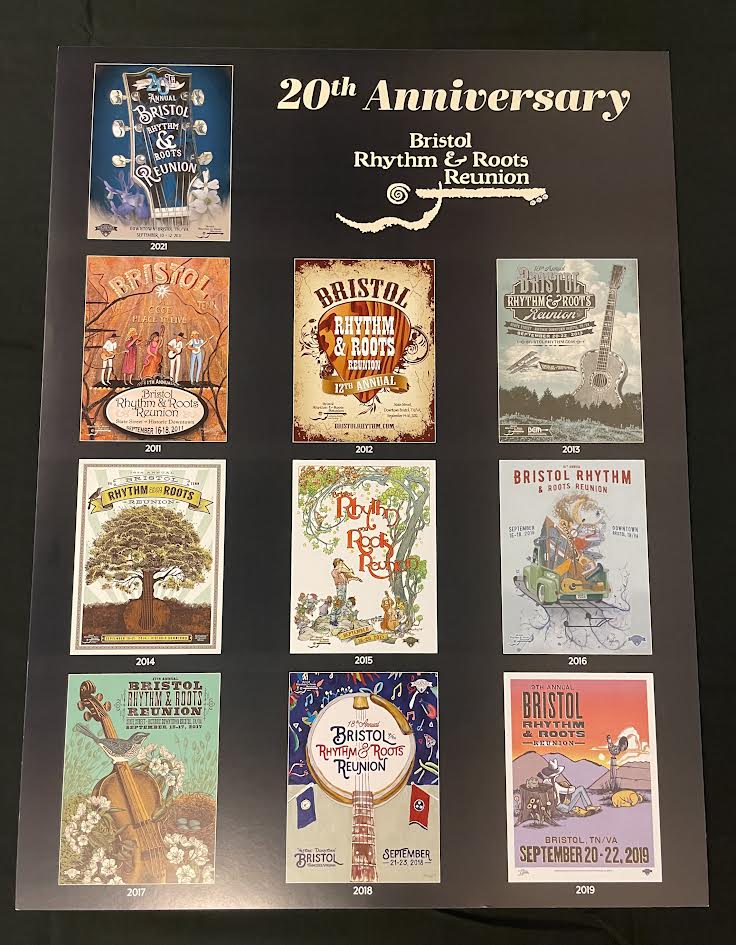

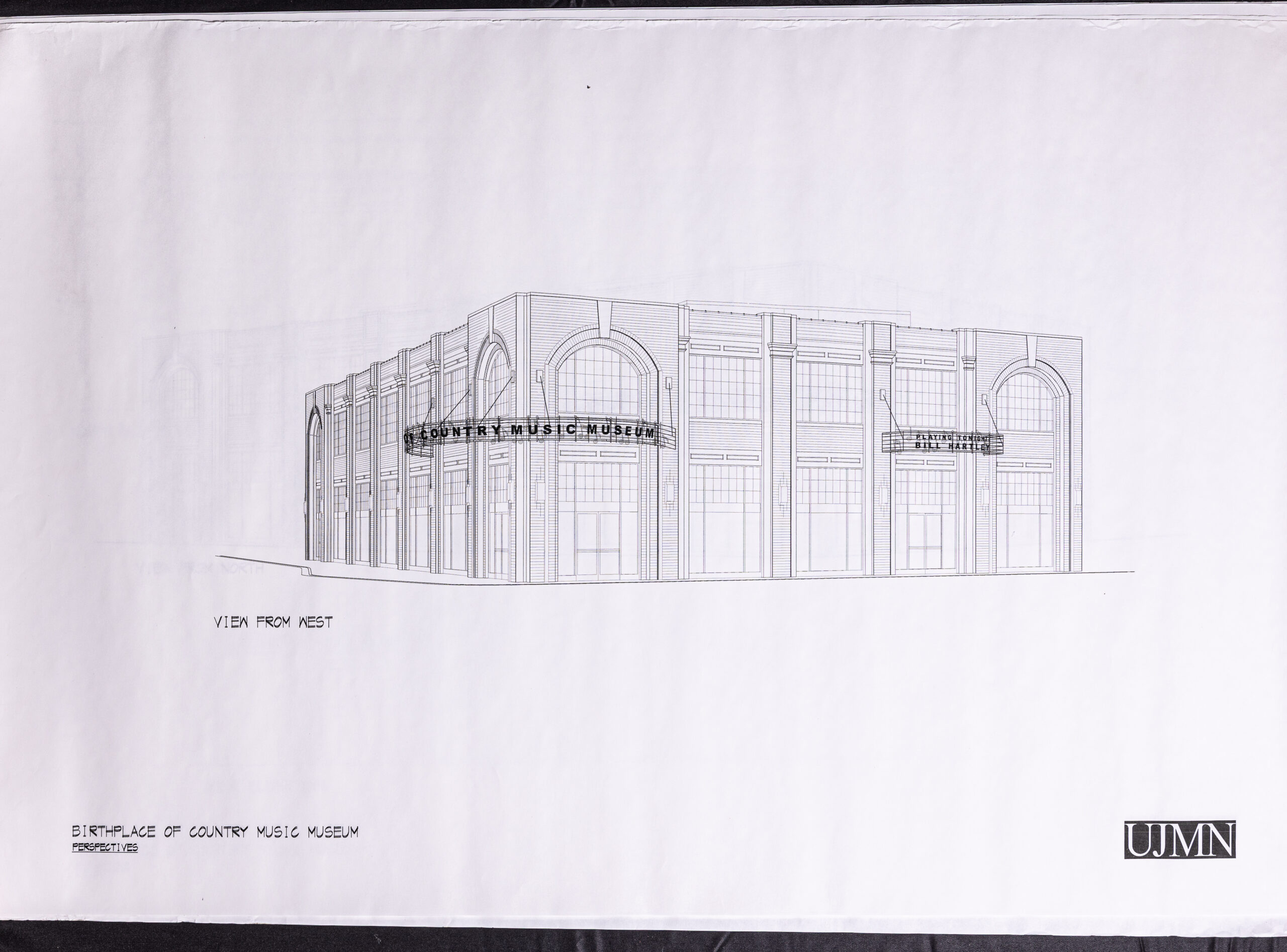

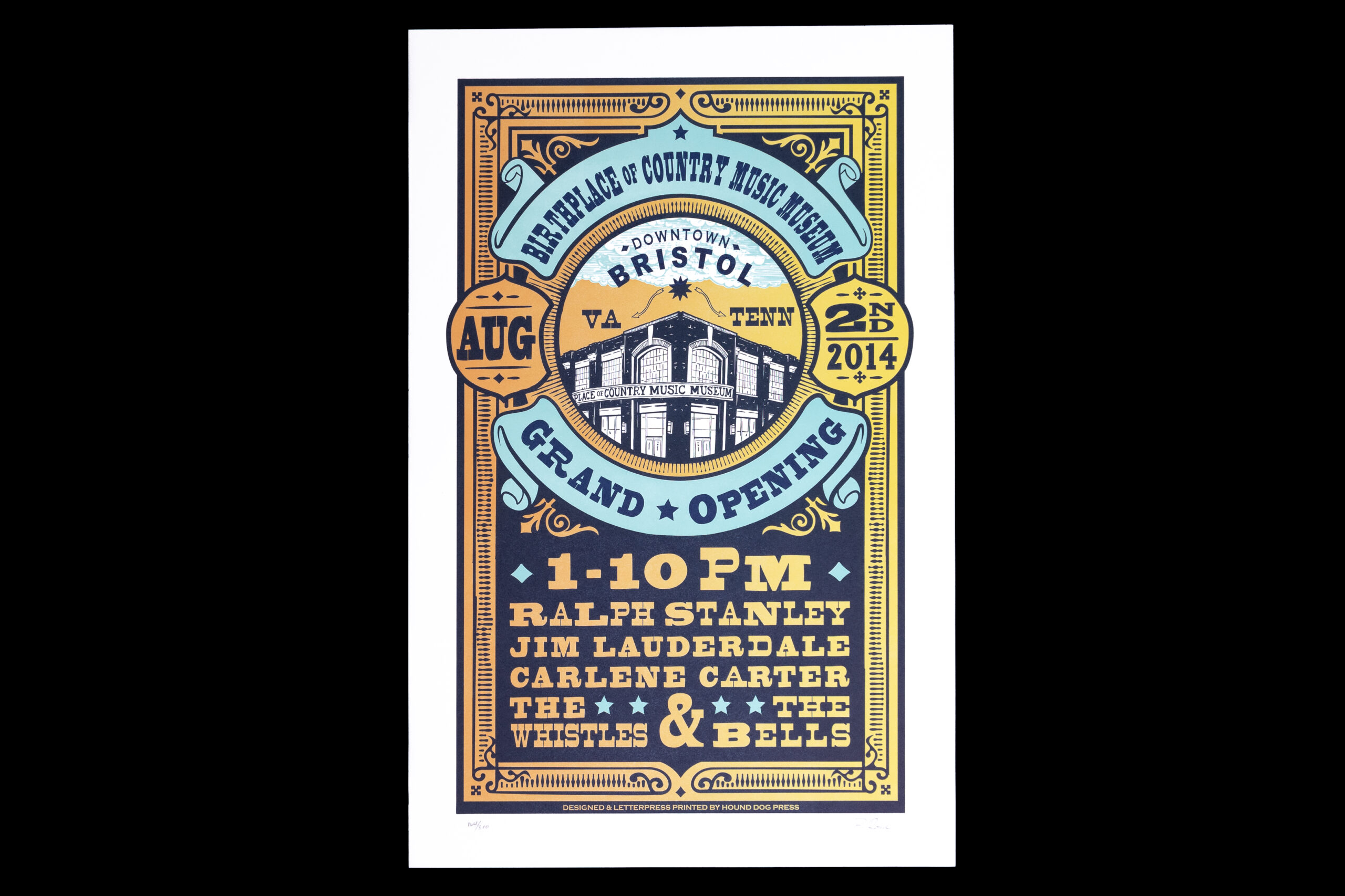

Decades later in 2001, the annual Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion music festival was established to honor the legacy of those seminal recordings. The Birthplace of Country Music Museum, an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, opened its doors to the public in August 2014. One year later, WBCM Radio Bristol went live on the air, broadcasting from the museum.

I relayed the story above to Rosanne’s manager, Danny Kahn, along with a request for this interview and extended an invitation for the artist to tour the museum while she is in town for the festival. He quickly replied, “Rosanne realizes how significant her visit to Bristol is. She has never been. She wants to do as much as possible regarding your requests.” From everything I had read, I was not at all surprised by her generosity.

So much has been written about Rosanne Cash and by her, so in this interview I chose to focus on her ties to our region’s music heritage, while adding a few trivial zingers à la Bop and Tiger Beat to satisfy my inner, pre-teen geek. Rosanne: if you are reading this, my apologies for that – but thank you for kindly playing along! I’m so grateful for the opportunity to make this connection for my hometown, and excited for you to experience Bristol and the festival. I hope you love them both as much as I do.

Below are my questions answered by the artist via e-mail:

This will be your first time performing at Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion and your first time visiting the museum. Knowing that your dad’s dream of having a museum dedicated to the legacy of the 1927 Bristol Sessions is now a reality, what are your thoughts?

He was right. I’m grateful that he spoke those words that day, and that a ripple of enthusiasm went out and planted the seed to create the museum, although, honestly, it seems like it was destined! Such a historic moment and location in the cultural makeup of our country deserves to be forever immortalized. I’m thrilled to be going to perform in Bristol and see the museum for the very first time. I’ve actually sent people there, but never been myself!

When tourists come to visit the museum in Bristol, we make it a point to encourage them to visit the Carter Family Fold in Hiltons, VA. We consider it hallowed ground, and it is poignant that your dad’s final performance was there. In the beautiful eulogy you wrote for June Carter Cash after her death in 2003, you mention that Johnny hosted a “grandkids weekend” for June on her birthday one year someplace in Virginia on the Holston River. Do you have any more memories of visiting there growing up?

In 2001, we visited the Maybelle and Ezra Carter house in Maces Springs, where June grew up, and which she and my dad owned in their later years. We went canoeing on the Holston River and had a celebration for June’s birthday on the property. All the children and grandchildren had to give her something that was not a physical gift— a song, a story, a wish of some kind. I remember I sang “The Winding Stream.” We visited A. P.’s grave and sang together on the porch. It was a wonderful weekend. When I was young, I remember going with Dad and June to visit some of her kin in the Valley and eating the best biscuits I’ve ever had.

This year is the 95th Anniversary of the 1927 Bristol Sessions, which many consider to be the most influential country music recordings in history. The themes in those old songs are universally timeless. Given your family ties, it makes sense that the music of the Carter Family would impact your own music, and in the past, you have cited them as an influence. Can you point to a particular Carter song – or songs – that most resonate with you?

Helen Carter spent a lot of time with me, teaching me the Carter Family canon, when I was 18 and 19 years old. It was an invaluable education. I loved “Black Jack David,” “Hello Stranger,” “I Never Will Marry,” “Sinking in the Lonesome Sea,” “Banks of the Ohio,” “Bury Me Beneath the Weeping Willow”— all classic and essential songs— but most of all, I loved “The Winding Stream.” I recorded that, and I also recorded “Bury Me Beneath the Weeping Willow” on my album “The List.” I still perform that song in concert and will be singing it with added poignancy in Bristol!

I once ran across an old video of a Carl Perkins concert from the 1980s.The Stray Cats were his backing band, and there you were – along with Eric Clapton, Dave Edmunds and George Harrison and Ringo Starr. You were the only woman on that stage, and you absolutely rocked “What Kinda Girl.” You have collaborated with so many amazing artists over the course of your career. What is it like to meet your heroes and to be respected as a peer among them?

As a pre-teen and teen Beatles obsessive, absolutely in love with and deeply affected by the Beatles, I couldn’t, in my wildest dreams, imagine being on a show with George Harrison, or becoming friends with Elton John, and singing for him at his birthday party, or so many other instances where I met the heroes of my youth, or a contemporary artist who inspires me. At some point, as a musician, after 40 plus years, you seem to run across everyone who is out there doing the same thing as you, like a person in a multi-national corporation who meets her colleagues in other branches of the company. 😉

You have been a big advocate for change on many issues, including artists’ rights to get paid fairly for the use of their music by tech companies like Spotify and Apple Music. You serve on the board of Content Creators Coalition, an artist-run nonprofit advocacy group for musicians. You have testified before the House Judiciary Committee in defense of artists rights on behalf of the Americana Association, as your dad had done in 1997 in support of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. With so many artists, artists unions, and political leaders pushing to enact reform, do you see change coming any time soon? Does more need to happen?

The Content Creators Coalition dissolved and morphed into the Artist Rights Alliance, on whose board I serve. Change comes, change is slow. I realize I’m working in a garden I may never see bloom, but we do have some small successes piled up lately, and intellectual property rights’ issues seem to have bipartisan support in Congress, which is hopeful.

The pandemic and the political climate in the U.S. for the past several years has forced many of us to re-evaluate our lives and careers. Artists were forced to get creative to keep their audiences engaged and are only just starting to recover from months of not touring. What effect has the pandemic had on you personally and as an artist?

I wrote—both songs and essays— and I enjoyed being at home. I realize I’m very privileged to be able to say that. I thought a lot about what I want to do in the next phase of my life—less touring, more strategic, important events, more writing, more staying put. I got Covid on the road, and it’s become an occupational hazard for touring musicians. It’s not just that, however— it’s that the lifestyle is not sustainable for me. I love the audience so much, and the community and connection, but the other 22 hours of the day are hard!

I follow you on Twitter and you are brilliant at it. You have an amazing sense of humor; your barbs are witty and razor sharp. It takes skill to effectively diss in a concise and timely manner and you nail it. When are you going to take the plunge to Tik Tok? You don’t have an account, but you are definitely in that space – people from all walks of life are dancing and singing to “Seven Year Ache” and “Tennessee Flat Top Box.” It’s a beautiful thing. Search your hashtag and give me your thoughts. I’ll wait…

Oh wow. My daughters send me Tik Toks all the time, and I enjoy them, but… it will be a learning curve for me, and also… how much time does one give to social media before it starts taking back from you…??

Because I rarely get the opportunity to fully embarrass myself in front of my heroes, I’m gonna go ahead and ask the hard-hitting questions nobody but me really cares about:

You’re alone in the house and it is on fire. You can only grab one thing before fleeing. What do you take?

Irreplaceable photos of my kids that aren’t digitized and family scrapbooks. It would be hard to leave behind my guitars and diamond earrings, but….

If you could have one superpower (that you don’t currently possess), what would it be?

Heal the trauma of every child in the world. (Then… play guitar like my husband.)

What is your recurring dream?

What is your recurring dream?

Giant waves are coming toward me.

What book are you reading right now?

“One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

What music is in your current rotation?

Wilco, the Avett Brothers, and Annie Lennox

What do you always keep in your purse?

A guitar pick, lipstick, and Pepcid.

What is your least favorite household chore? Favorite?

Emptying the dishwasher is my least favorite. I love sweeping and cleaning out drawers.

What is your favorite movie?

Hmmm… probably “All About Eve.”

Are you a cat person or a dog person?

I have a cat I love, but I like dogs better, generally.

Do you believe in ghosts? Aliens?

The jury is still out. Ghosts…not traditional-type ghosts, but energy that survives, and the resonance of people and places that survive death or destruction. I believe that because energy doesn’t die. Aliens…? It’s a statistical impossibility that we are alone in the universe, but I have no idea what form that takes.

Marvel or D.C. Comics?

Ooh. I don’t know. Not my area.

Toilet paper rolled out or under?

No opinion on that.

What is your spirit animal?

The ocean.

Favorite toy as a kid.

Chatty Cathy doll

You really are a Renaissance woman. You continue to accomplish so much and seem to have a deep well of creative reserves. What’s next for Rosanne Cash?

I’m the lyricist on a new musical called “Norma Rae,” based on the bio of the real woman who became Norma Rae in the film starring Sally Field. We are staging a workshop with full cast in September, and I’m excited. I love working collaboratively like this.

Thank you so much for your time and consideration! I really appreciate this opportunity!

See you in Bristol!

I highly recommend reading Rosanne Cash’s memoir, “Composed,” and “Bodies of Water,” a collection of short fiction stories. Catch her performance on the State Street Stage on Sunday, Sept. 11 at 5:15 p.m. EDT during Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion. The Stage is located right beside the monument to the 1927 Bristol Sessions on the “Tennessee side” of State Street. Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion is scheduled for September 9-11, 2022, on State Street in Historic Downtown Bristol. Visit BristolRhythm.com for lineup and ticket information.

What is your recurring dream?

What is your recurring dream?